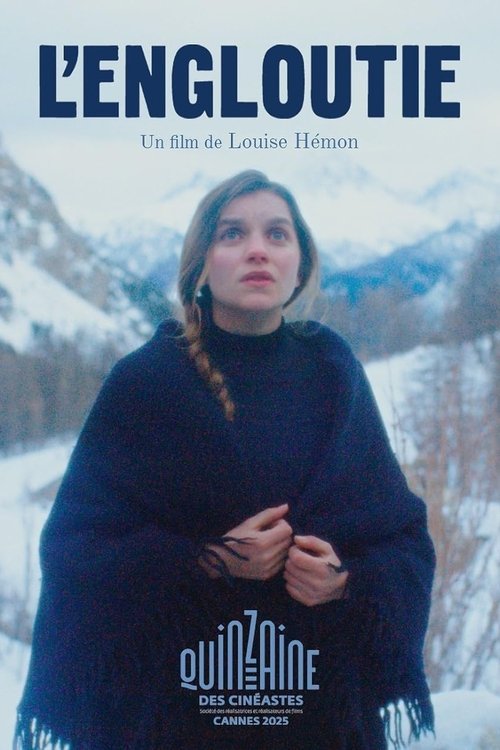

When a filmmaker tackles a project that has a personal connection to the story, there’s always a risk that the director could be too close to the material to do it justice. And that would seem to be the case with the debut narrative feature from filmmaker Louise Hémon, who’s best known for her documentary work. However, that shift in genre does not seem to be the primary issue with this offering. The problem here is more contextual; indeed, it would appear that the director could be so acquainted with the subject matter that she assumes her audience may have the same degree of familiarity with it as she does and that her cinematic interpretations of the material would be comparably understood accordingly. As a French filmmaker dealing with French material, that might be true for audiences of French viewers. But, for those from outside France or unfamiliar with late 19th Century French history and culture may easily find themselves lost (note my raised hand here). Set in the winter of 1899, the picture tells the story of a teacher (Galatéa Bellugi) from an apparently cosmopolitan background who arrives in a small Alpine hamlet populated by largely uneducated, homespun residents who jealously cling to their traditional folk beliefs and assorted superstitions. She attempts to broaden the horizons of her students and their families, only to find resistance to her radical ideas from the outside modern world. And, when the community begins experiencing a series of avalanches and mysterious disappearances, residents begin to suspect that she and her newfangled ways might somehow be the cause, one that must be stopped. It’s a scenario reportedly similar to the experiences of the filmmaker’s ancestors, who themselves once served in similar teaching capacities. It also creates a narrative that feels like a loose cross between “Midsommar” (2019) (or would that be “Midwinter”?) and “Vermiglio” (2024). But the specific events in this story never make any of this especially clear. The result is a seemingly random, glacially paced, visually meandering tale that feels somewhat like an exceptionally slow-burning horror film but that never quite feels confident enough in itself to make the leap necessary for enthusiastically embracing such a definitive approach. To make matters worse, the film is often too dark – literally – excessively drawing upon dim lighting with candles, torches and fireplaces that’s so subdued that it’s frequently difficult to identify the action unfolding on screen (ambiance is one thing, but indiscernibility is something else entirely). Given the foregoing, “The Girl in the Snow” regularly comes across as not being up to the task of carrying out what it’s allegedly attempting to achieve. Indeed, in light of that, it would seem that it might truly be best to stick with what one does best than to stray far afield into new and uncharted territory.